Blog

Welcome!

Please read and comment on the entries that follow. The most current one will be highlighted on this page; earlier entries can be found under the archives link below.

Change We Could Believe In?

January 05, 2010

As the New Year gets underway, the housing market’s continuing

weakness and the Obama Administration’s loan modification plan’s poor

performance have refocused attention on what better ways there might be

to prevent foreclosures and keep people in their homes.

The urgent need for change is clear:

- The Making Home Affordable mortgage

modification program has produced close to 700,000 trial modifications,

but to date only about 30,000 of those have been finalized. We won’t

know until well into 2010 whether the Administration’s initiative in the

3rd quarter of 2009 significantly accelerated these conversions or not.

- Meanwhile foreclosures in 2009 likely will reach 2 million. There

is no indication that 2010 will be significantly better, as loan

performance, particularly among prime borrowers, continued to weaken

through 3Q09.

- The Comptroller of the Currency’s last report on the performance of modified loans

documents that an alarming 61 percent of all borrowers that had

received any kind of modification—through the Obama plan or directly

from the lender—were seriously delinquent 12 months after the

modification. Loans modified in the third quarter of 2008, when actual

reductions in interest rate and principal were more common, show a

significantly lower early redefault rate, suggesting that their

long-term performance will be better, but still suffer from significant

redefaults as currently structured. Too few Making Home Affordable loan modifications have been finalized to know how they will perform.

- Significant numbers of borrowers across the credit spectrum owe more

than the current market value of their homes. These “underwater”

mortgages make it difficult for families to move for employment or other

reasons, or to refinance for a lower rate.

- A study by the New York Federal Reserve concluded that modifications that reduced payments by reducing prinicipal performed better than those that reduced payments through interest rate reductions.

Shifting the focus of the Making Home Affordable program to

principal reductions, rather than interest rate reductions, offers an

immediate step that could improve the program’s success rate, give

borrowers a more attractive long-term stake in their homes, and reduce

the long-term handicap assisted borrowers face when their loans remain

underwater.

Principal reductions, however, face some potent obstacles.

- Moral Hazard Principal reductions, this argument

goes, encourage borrowers to renege on their obligations. Ultimately,

it continues, this will increase borrowing costs for everyone, as

lenders charge for the risk of nonpayment of principal. Borrowers who

can still make the scheduled payments on their mortgages will stop doing

so in order to qualify to have their total obligation reduced.

Neighbors who don’t receive help will resent those that do, and

like-situated households will receive differential treatment of their

obligations simply because one chooses to make their payments and the

other doesn’t.

Moral hazard is a serious problem that needs to be

addressed. But it can be managed and contained by using the same

criteria that have been applied to the current interest rate writedowns,

limiting it to a owner occupants in homes below a ceiling value, that

were originated before the start of the modification program, for

instance. The current program poses similar issues—some borrowers get

their interest rates reduced, others do not. It’s not fair. Public

policy is full of “borderline” issues where only a small difference

separates those who receive support and those who do not. Helping

borrowers stay in their homes creates broader social benefit by reducing

foreclosures, vacancies and blight. Stabilizing neighborhoods and home

prices benefits every owner in the neighborhood.

Moreover,

many of the loans made at the height of the housing bubble were inflated

to begin with, sometimes with extraneous charges and bogus fees, and

yield spread premiums to brokers paid for by borrowers. They were made

possible only by qualifying borrowers with artificially low rates while

lenders knew they would be unable to make payments on the ultimate,

higher rates. And so on. In this case, where is the moral hazard: on

the borrower that has been victimized by crappy underwriting and

dangerous products, or on the lenders who should have known better?

- Write downs Forgiving principal on the loan means

that the investor holding the mortgage has to take a write down on its

value. Lenders and investors hate this. But in the current

modification program lenders and investors already are accepting a real

loss of anticipated return on their loan by accepting a lower interest

rate. What they are avoiding is having to recognize a loss today on a

loan they are still holding on their books. But if the net present

value of a principal write down to the borrower is greater than a

foreclosure is likely to net, then it is no different than the costs

lenders already are willing to bear in reducing their note rates. If

the government used its Making Home Affordable funds to match

write downs of principal, it surely would reduce lenders’ asset value.

But it could provide a far greater return through stabilization of the

housing, increased likelihood of a successful modification, and

restoration of equity potential for the borrower.

Write downs

could force lenders to increase their capital again, as the value of the

assets they hold are reduced by the principal reductions. But if the

assets they hold are being artificially propped up through modifications

that ultimately won’t succeed, or that leave the borrower in a

long-term negative equity position that keeps them locked in their

homes, isn’t it better to take the pain now and deal with it, rather

than allow zombie portfolios to stumble along while hoping that time

will wipe out the problem?

- Participation Lenders are voluntary participants in the Making Home Affordable program.

Requiring principal reductions could drive them out of the program.

But the banking sector continues to benefit from the wide array of

liquidity efforts that support the system. These could be used to

“encourage” lenders to participate. Also, as the crisis has dragged on

and more borrowers seem to be willing to walk away from their underwater

mortgages, lenders’ attitudes about principal reduction ought to be

changing. Taking a calculated hit now surely is a better choice for

shareholders and the nation than gambling on a much greater loss down

the road.

In point of fact, lenders are already making principal

reduction modifications. In the New York Fed study sample, 7 percent

received principal reductions, averaging 20 percent. The OCC report

states that 13.2 percent of the modifications in 3Q09 received them.

This is an increase over 10 percent in 2Q09 and 3 percent in 1Q09. By

far the largest share of these—37 percent of all modifications they

made—were offered by lenders holding the loans in portfolio. A

negligible number—rounded to 0.0 percent—were made for loans held by

investors. This suggests where the pressure needs to be applied most

heavily—on the securities portfolios and on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac,

who together did only 134 compared to 17,259 by portfolio lenders. Why

are portfolio lenders so much more willing to offer principal reductions

in their own modification programs?

The drumbeat for some kind of change is growing. The New York Times’ January 5 editorial concluded

that “To avert the worst, the White House should alter its

loan-modification effort to emphasize principal reduction.”

Sounds like change we could believe in.

Read more...

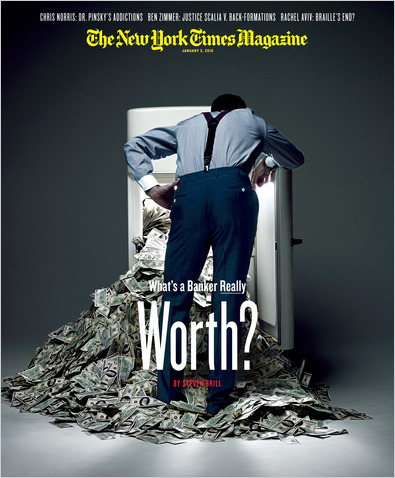

Setting Pay at Bailed Out Companies

January 03, 2010

Steven Brill’s long January 3, 2010 New York Times Sunday Magazine piece on Kenneth Feinberg’s experience in setting executive pay at the “TARP

7,” as he calls them, illuminates how wide the gulf between top compensation at financial companies and the plight of working Americans really has become. This should be must-read material for anyone concerned with social justice in America.

It also highlights the discouraging lack of progress that has been

made to date in cementing real reforms in the way financial companies

are run and their leaders compensated. If the near-collapse of the

world’s financial system isn’t enough of a goad to get this done, what

is?

The most telling part of this long piece is AIG’s representation that

it would be unfair to force its executives to take the lion’s share of

their compensation in company stock, because it is “essentially

worthless,” as its vice-chair is quoted as saying. The compromise

Feinberg adopted retained the structure, but perhaps not the substance,

of his original demand. But all the worker bee suckers in AIG—and by

extension all the other companies under Feinberg’s supervision—probably

won’t have the chance to shift out of the “essentially worthless” stock

in their ESOPs, or maybe in their 401(k)s, if they’re really unlucky.

And the folks who lost their jobs and homes as a result of these

financial companies’ mistakes won’t get any “do-overs,” either.

House Financial Services Chairman Barney Frank (D-MA) is at his best

in this article, a refreshing voice of genuine progressivism. We can

only hope that his sensible and straightforward observations about this

compensation adventure spreads to more of his colleagues.

Also in this Sunday Magazine is a provocative piece

by Matt Bai considering the distance between the populist demands of

the Democratic left and what Bai calls the President’s “progressivism.”

These two bookends of the Magazine offer a sobering start to the new decade.

Read more...

How Big a Problem is Mortgage Fraud?

December 27, 2009

Whether you find a recent post on the blog Seeking Alpha completely persuasive or not, it’s a useful reminder that at least part of the reason for the mortgage crisis was fraud, pure and simple. (Thanks to former colleague John Fulford for linking me to this post.) Whether through predatory use of unsuitable products to churn mortgage debt through unsophisticated/greedy/ignorant homebuyers/refinancers, through total misrepresentation of a borrower’s qualfications in order to write a loan and earn a fee, or through blatant disregard of investors’ terms and conditions for qualified loans in securitizations, there can’t be any doubt that the mortgage system at the height of the housing bubble was riddled with fraud.

Hopefully, aggrieved investors will prosecute those who defrauded them. Hopefully, as Seeking Alpha suggests, we’ll see some perp walks and folks learning how to accessorize orange jump suits.

But what to learn from all this, and what to do about it in the future?

- When investors require reps and warrants, they must put in place

reliable quality control systems to actually check whether their

counterparties are playing fair. Folks inside every

securitizer/investor/lender will push back on tough QC procedures—they

alienate the client, they push business to others with fewer qualms, “my

comp is based on what I sell, and your dumb procedures are costing me

money.” The example cited in the Seeking Alpha post make it

clear that the fraud was there to be found from the start. Why should

it take a forensic review of the securities to ferret it out? Unless

the mortgage industry gets way more serious about how they review and

manage counterparties, the sheer volume of the US housing market is an

open invitation to commit fraud. Chances of being caught are small, the

cost of paying up can be negligible, and if the risks are sliced into

dozens or scores of pieces held by hundreds of investors, who’s gonna

know or even care?

- Every player in the mortgage conveyor belt should get paid not for

production but for long-term performance. Brokers can be paid a portion

of their fee on delivery, the rest over the first three years, when

early payment defaults are most likely to show up. If they underwrite

solid borrowers, they will get paid. If they cheat or cut corners, it’s

their compensation that’s at risk. The same right on up the chain.

During the height of the boom a secondary market colleague who should

know told me one of his customers replied to voiced concerns about

credit quality in the loans he was delivering, “Hey, we are simply a

conveyor belt. We move the loan from the originator to you. The rest

is not our problem.”

- Housing and mortgage counseling by unrelated parties should be

mandatory for any low downpayment or equity stripping refinancings.

First time homebuyers are especially vulnerable, but owners suckered by

refinancing offers also ended up with toxic mortgages that are putting

them out of their homes.

- Disclosures at loan settlement should be clearer than they are

today, and delivered to borrowers with plenty of time to review them.

The Federal Reserve Board recently closed a months-long comment period

on changes to its Regulation Z, covering Truth-In-Lending disclosures.

They recommended a heap of really good changes. They’ve received

strong support from Consumer Federation of America, National Consumer

Law Center, Center for Responsible Lending and others. (Check out the Fed’s regulatory pages to see copies of these and other comments on the proposed rule.)

Read more...

New Sheriff In Town?

December 23, 2009

With close to 30 percent market share and razor thin capital margins, the FHA is in greater need of tough oversight and management than perhaps ever before. Happily, HUD Secretary Shaun S. Donovan and his FHA Commissioner, David Stevens, seem to understand this.

In the face of fears that FHA’s rocketing share of single family

financing is drawing in many of the unscrupulous brokers who plagued

subprime lending in recent years, the agency has adopted a new “get

tough” policy and is using its administrative authorities aggressively.

A recent article in National Mortgage News chronicles this recent activity. The Donovan quote from a consumer group meeting is actually from Consumer Federation of America’s annual Financial Services Conference earlier in December. You can see the whole speech on C-SPAN. It’s good to have a new sheriff in town!

Read more...

Next Steps for Fannie and Freddie?

December 23, 2009

Next Steps for Fannie and Freddie?

The Financial Times

yesterday today published a summary piece on what’s likely to happen

next to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Obama Administration has

committed to laying out options in its February, 2010 budget

submission. But the folks responsible for producing them may rue this

promise made earlier in 2009 when the rest of the Administration’s

financial modernization package was unveiled.

The government’s unprecedented and aggressive support for the the

mortgage markets hinges almost entirely on the continued role the two

companies play in the market. The private securitization market is

dead. Recent research from JP Morgan suggests that it will remain that way from some time to come.

The Federal Reserve’s $1.25 trillion purchase program for Fannie

and Freddie MBS is supposed to wind down in the first quarter of 2010.

But many observers doubt they will be able to do so in the face of

likely political opposition to moves that could raise interest rates for

consumers, as phasing out the program might do.

The two companies also are playing a crucial role in

administering the Administration’s Making Home Affordable” mortgage

modification program. Once restructured, it isn’t clear how that

capacity could be easily replicated.

Perhaps because they were the first crippled financial patients

to go under the knife in 2008, the terms of their government assistance

are significantly more onerous than those that Bank of America and other

major lenders had to agree to. The dividend on the preferred stock

held by Treasury in return for its investments in the two companies—now

totaling $112 billion—is 10 percent, for instance, higher than that

imposed on other bailees. Neither company is likely to be able to pay

back what they owe, in addition to their divident payments, anytime

soon.

It can be argued that the government has the two companies

exactly where it wants them: firmly under government control, but not

on the government’s balance sheet. They can be used to further public

policy goals without interference from shareholders or private owners,

at a time when the government has few similarly powerful direct levers

to work in the economy.

So the question essentially should come down to this: what is

the rush to alter the current structure? With many trillions of

outstanding MBS under their guarantee, and a combined market share

exceeding 70 percent now, a great deal of the housing market’s immediate

and near future health seems likely to ride on the two companies and

the market’s faith in their guarantees on the securities. And the only

way to guarantee that for the moment, it seems, is through the continued

support of the current system, however creaky it may be.

The

Financial Times piece summarizes a series of potential paths the

Administration could choose. Having spent many hours over the last year

with colleagues in the progressive policy sector trying to develop a

workable successor model, I’m skeptical of their chances for success in

the short run. I look forward to working with them, and hope that

something durable and workable can emerge. But mostly I’m anxious that

politics and theory are not allowed to trump pragmatism when it comes to

the question of timing. Rushing to a solution merely for the sake of

having one is not the right path.

Read more...

Page 12 of 16 pages

<

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

> Last

Blog Archive >>